Christian nationalism: A Baptist evaluation and response

Christian nationalism: Does such a thing exist? If it does, what is it and how did it emerge? Is it a threat? How should we respond to it?

To answer these questions, I do not offer a political treatise representing partisan politics. The motivation is theological and ecclesiological, not political. However, as is sometimes the case, a careful review of our faith and tradition requires us to reassess how we engage with the public square. So there is no avoiding political inference and implication.

There are times when the ways of God’s reign are at cross purposes with the ways of worldy systems of governance.

Ronald Cava

To paraphrase Leonard Sweet and Frank Viola, Jesus is not the chaplain for any political party. Neither the left nor the right holds a patent on the influence or power of Jesus. Jesus did not come to establish a political utopia on earth. They quote Origen who said, Jesus is autobasilia, that is Jesus himself is the kingdom.[i]

This offering represents my deep convictions as a Christian, a Baptist and an American, in that order. It is based on my reflections from Scripture and theology, secular and Christian history, and specifically in light of our Baptist heritage and distinctives.

At heart, this is my humble pastoral effort to educate and elucidate our congregation about this issue. In so doing, I hope to inspire us, as Baptist believers, to reassert our longstanding and historical allegiance to the ideals of complete religious liberty for all people and to the sound principles of the separation of church and state.

Introduction

I first began receiving questions about Christian nationalism during the 2016 election season. I began to craft a response at that time but decided the threat was not severe and addressing it would threaten the stability of our congregation. I was wrong. This is a Jesus moment in America.

“I decided the threat was not severe and addressing it would threaten the stability of our congregation. I was wrong.”

Michael “Chip” Rotolo grew up here at First Baptist Church. He has quickly made a mark as a thoughtful and respected research specialist at the Pew Research Center. Pew is a trusted, nonpartisan, nonpolitical, nonadvocacy think tank. Their mission is “to inform, not prescribe.” Their founding documents say, “Fact-based information is the fuel democracies run on — the raw material from which societies identify problems and construct solutions.” Their work often examines religious and faith-based issues.

Rotolo recently collaborated on a report titled “Christianity’s Place in Politics and Christian Nationalism.” In this fine report, Pew revealed: “An overwhelming majority of Americans — 83% — say the government should not declare Christianity the official religion of the country. Only 13% of Americans support declaring Christianity as the national religion.”[ii]

Yet nearly every day we are hearing of new legislation or edicts from politicians that seem contrary to that opinion. The current speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, envisions himself as the new Moses, who will lead America out of bondage. Television pastors and other religious celebrities populate their books, sermons and social media posts with content that marks them as Christian nationalists.

These discrepancies between majority American opinion and political currents are indicative of the threat of Christian nationalism.

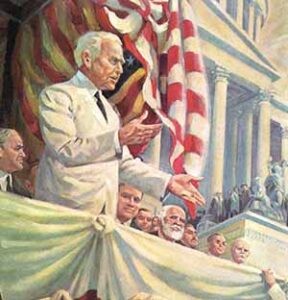

Edwin Hearne’s painting of George W. Truett delivering his 1920 address “Baptists and Religious Liberty” is part of the Eight Great Moments in Baptist History series. (SBHLA Image)

What is Christian nationalism?

We first need to ask, what is “nationalism”? Nationalism, on its own, is not a bad thing. Properly understood, nationalism is nothing more than the sharing of a set of values and a common love for one’s own country of habitation.

Nationalism, thus understood, provides the glue that holds together civilized societies. It does not imply that everyone must think or believe alike. Nor does it mean new neighbors coming from other countries must abandon sincere expressions of their native culture. It does mean, for us as Americans, that all of us in this vast and increasingly pluralistic society can love our country and be loyal to it without disenfranchising one another.

“All of us in this vast and increasingly pluralistic society can love our country and be loyal to it without disenfranchising one another.”

Nationalism, as such, is rather generic. However, like anything else, nationalism has been and can be subjected to extremism.

We must be wary, for instance, of it morphing into ethnic or racial nationalism as it has throughout history. We must not forget the lessons of the two world wars, when the catalyst for so much suffering was the ideal that a specific ethnic race of people was superior to all other races.

Nor should we neglect more recent manifestations such as the Jim Crow era of American history, when people of color were regarded as less than fully human and therefore not fully celebrated and integrated citizens of this United States of America.

This is a terrible stain upon our history, and not fully faded.